Unk., Edmonia Lewis.

Many readers love posts about women artists as much as I love finding the history and images to share. The story of Edmonia Lewis is one of the most compelling and inspiring I have found yet. click on the photos for links to their sources.

Edmonia Lewis was born in the mid-1840s and died sometime after 1909. It appears her father was a free African from the West Indies and her mother was a Ojibway mother. Edmonia told interviewers that her given Ojibway name was “Wildfire.”

Along with a brother, Edmonia was orphaned at a young age. Her older brother Samuel became a successful businessman in Bozeman, Montana, and financed Edmonia’s secondary education at Oberlin College—the first American institution to admit women and African Americans.

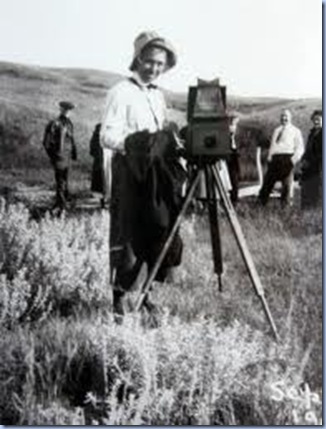

Here are two photographs of Edmonia taken by Henry Rocher about 1870, and currently in the collection of the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, D.C.

Edmonia faced discrimination at Oberlin College and left before she graduated. But she knew what she wanted. Again with her brother’s help, she went to Boston to study with the neoclassical sculptor Edward Brackett. Like any artist, her career was a combination of extremely hard work, garnering patrons, and networking.

Many of Edmonia’s friends were members of the American abolitionist movement. Eventually, and against tremendous odds, she began to establish a name for herself as an artist facing three social obstacles: being female, African American, and Native American. She publicly identified herself with these threads of her identity, and chose subject matter that held meaning to oppressed people and women.

Two of her earliest works depicted the abolitionist martyr John Brown, and Robert Gould Shaw, the white commander of an all-black regiment in the American Civil War. Partially financed with the sale of these pieces, Edmonia traveled to Italy to further her career. In Rome, she joined a community of American sculptors—including several notable women—and occupied the former studio of the Italian master Antonio Canova.

Here is a study of Moses, made after the masterpiece by Michelangelo, completed during Edmonia’s time in Rome.

Edmonia Lewis, Moses (after Michelangelo), 1875. Smithsonian Institute.

Fearing that others would not believe her work was truly her own, Edmonia shunned the practice of roughing out her sculptures and hiring Italian artisans to carve them. Instead, she completed all her own work.

One piece created during her time in Rome was the bust of Henry Wordsworth Longfellow, below. Inspired by the poet’s work, “The Song of Hiawatha,” Edmonia had already created sculptures based on his Native American themes. When she heard that the poet was visiting Rome, she found him in the street, studied his face, and created this bust.

Edmonia Lewis, Bust of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, 1872.

This sculpture, Hagar, was also made in Rome.

Edmonia Lewis, Hagar, 1875.

In 1876, Edmonia Lewis sculpted what is known as her masterpiece, The Death of Cleopatra. This interpretation of the fallen queen stands out because it shows her, vulnerable and stricken, just after being bitten by the asp. The piece generated a stir when it was shown at the Philadelphia Exposition in 1876 and again at the Chicago Interstate Exposition two years later.

Edmonia Lewis, Death of Cleopatra, 1876. Smithsonian Institute.

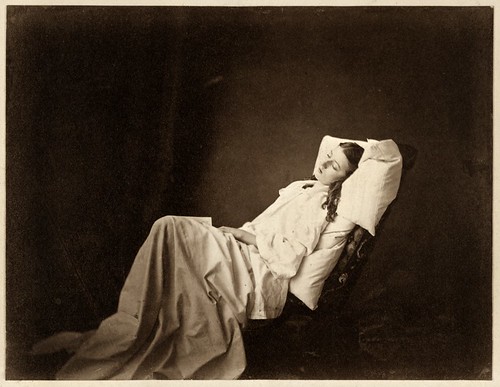

Another important work is Asleep, below. This is one of four cherub pieces created around 1870. Asleep won a gold medal at the International Exposition of Paintings and Sculpture, held at the Academy of Arts and Sciences in Naples.

Edmonia Lewis, Asleep, San Jose (CA) Library.

There are many sources of biographical information on Edmonia Lewis on the Internet. I’ve used the one I thought was the best researched and most credible, here. Please click on the link for much more information about this amazing, inspiring American artist.

"Some praise me because I am a colored girl, and I don't want that kind of praise. I had rather you would point out my defects, for that will teach me something."

Edmonia Lewis to Lydia Maria Child.